In my Twitter timeline, I saw a post praising a recent New York Times article on graduation rates and the devalued high school diploma. Since I had written a blog criticizing the many (and typical) flaws in the piece, I nudged Stephanie Banchero and Nichole Dobo to reconsider.

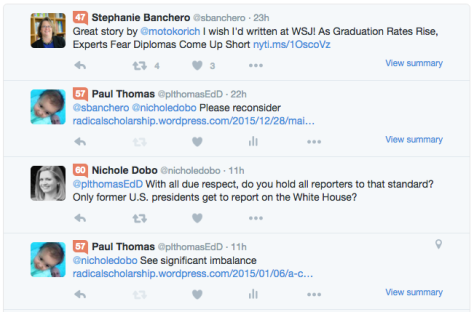

Dobo was gracious enough to respond [1], but Twitter really doesn’t afford the space to make my case as well as both the topic and Dobo deserve so I want here to lay out better just exactly why so many of us in education are routinely frustrated with how media cover education.

Let me start by reemphasizing why educators have moved from frustrated to exasperated in terms of media coverage of public education.

In the mid-1800s as public schools became a more compelling option for education in the U.S., Catholic schools initiated scathing attacks on public schools—not for educational, but for market reasons.

The history of vilifying public education in the U.S. has replicated that pattern until today—although the negative drumbeat has intensified significantly over the past three decades of high-stakes accountability (which is mostly a political, not an educational, venture).

Therefore, most political and media commentary on public education is misguided. Yes, most.

The problem for educators is not that public education is without flaws and is being unfairly demonized, but that we in the U.S. have mostly failed public education (and our students, and our country) by continuing to wallow in false narratives while ignoring the very real problems in both our education system and society that warrant reform.

My argument is that since most political leaders and political appointees governing education as well as most journalists covering education are without educational experience or expertise, these compelling but false narratives are simply recycled endlessly, digging the hole deeper and deeper.

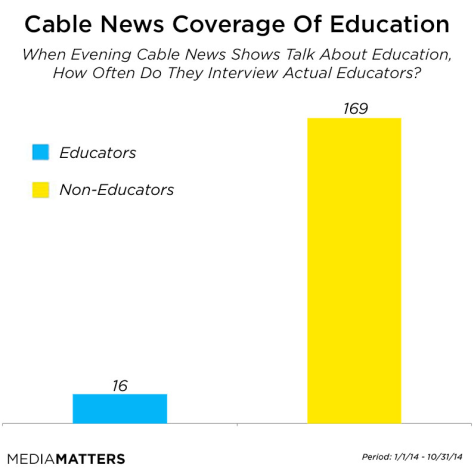

Compounding that problem is the overwhelming evidence that journalists covering education disproportionately turn to people outside the field of education as their sources [2].

Think tank advocacy masquerading as research (rarely peer-reviewed) garners sensational headlines [3] while psychologists, economists, and political scientists are quoted about every aspect of education.

And on the rare occasion that I am interviewed by a journalist, I can predict what will happen: the journalist is always stunned by what I offer, typically challenging evidence-based claims because they go against the compelling but false narratives.

No, there is no positive correlation between educational quality and any country’s economy.

No, teacher quality is actually dwarfed by out-of-school factors in terms of student achievement.

No, charter and private schools are not superior to public schools.

No, school choice has not worked, except to re-segregate schools.

No, merit pay does not work, and is something teachers do not want. Teachers are far more concerned about their autonomy and working conditions.

No, standards do not work—never have—and high-stakes testing is mostly a reflection of children’s lives, not their teachers or their schools.

This list could go on, but I think I have made my point.

Now let me offer what I think is possibly the best example of the problem—reporting of the SAT.

For decades, the College Board reported SAT scores, ranking states by their average score. The media participated then in the annual bashing of schools based on those rankings.

Eventually, the College Board conceded that such rankings are deeply flawed since among the states, the percentages of students taking the test make those comparisons/rankings invalid—and the SAT is not designed to measure the quality of schools in a state (the SAT is designed only to predict first year college success and does so slightly worse that GPA).

Thus, the College Board issued a notice [4] and began releasing state SAT scores alphabetically. However, the media persist in the bashing.

Another problem with journalists covering education is a journalism problem: seeking to address “both sides” of issues in order to appear fair and balanced.

Therefore, I have invoked the Oliver Rule because that practice too often is not being objective and mostly distorts (as John Oliver brilliantly exposes about climate change) the real balance between the credible and the baseless.

Some, possibly many, issues simply do not have two sides, and often within fields—while there remains debate—issues have such an overwhelming body of evidence supporting a stance that posing the topic as “debatable” is terribly flawed. Framing an issue with someone who is credible and someone who is not fails reporting and the public.

For example, I struggled with the media about corporal punishment recently because the topic simply has only one side (corporal punishment is overwhelmingly harmful), yet every journalist sought both sides for the reporting. This was replicated when I addressed grade retention as well.

Since the U.S. suffers under the delusion that mainstream media is liberal (it isn’t), I must stress that even the so-called liberal New York Times, NPR, and even Education Week are more apt to misrepresent education than swim against the compelling but false narratives.

As I have examined (and had reaffirmed with NPR once again covering Sal Khan as if he is a credible educator in recent days), NPR follows the patterns I have detailed above when covering “grit.”

Where education journalism thrives is in the New Media (blogging) and alternative media (AlterNet, Truthout, The Conversation). In fact, note that Valerie Strauss’s The Answer Sheet (a blog at the Washington Post) is far superior to the print education reporter Jay Mathews, who works within the false narratives about education.

So to return to Dobo’s engaging with me about my concerns.

Dobo and I share something important: we want to defend our professions because they both matter mightily. On that, I agree with Dobo and respect her integrity and her field.

To her challenges to my claims, I want to clarify that, yes, I do believe education journalism would be greatly improved if journalists covering education had expertise and experience in the field.

I have been a coach, and also believe coaches are better when they have played the game they are coaching.

But, my main contention is that currently and historically almost all the politicians governing education, pundits pontificating on education, and journalists covering education have little or no experience or expertise in the field.

My modest proposal is that most should—but certainly not all.

And then, more directly, I also must stress that the real problem with education journalism is that the sources of education coverage in the media are the same talking heads without experience or expertise—think tank leaders, edupreneurs, education hobbyists (mostly millionaires and billionaires), anyone except educators.

Few people are more critical of my field of education than I am so my real concern is that journalism is failing the real reform needed in schools because of the experience and expertise vacuum in the media covering education.

Education needs a critical media, journalists who resist the false but compelling crisis narratives being recycled by politicians.

It is well past time, I think, for everyone who wants to understand education to try asking a teacher. And then listening when what we explain goes against conventional wisdom.

—

See Also

Is It Journalism, or Just a Repackaged Press Release? Here’s a Tool to Help You Find Out, Rebecca J. Rosen

[1] The conversation, in part, included:

[2] See Educational Expertise, Advocacy, and Media Influence, Joel R. Malin and Christopher Lubienski; The Research that Reaches the Public: Who Produces the Educational Research Mentioned in the News Media?, Holly Yettick; The Media and Educational Research: What We Know vs. What the Public Hears, Alex Molnar. And REPORT: Only 9 Percent Of Guests Discussing Education On Evening Cable News Were Educators:

[3] Consider this press release from the Center for American Progress (CAP), with prompting at the end to talk with their experts, and this review, discrediting the report praised in the press release. The CAP report speaks to the false narratives, and thus, is poised to resonate with political leaders and the media—while the review is likely to garner little attention.

[4] The College Board warns: “Educators, the media and others…[s]hould not rank or rate teachers, educational institutions, districts or states solely on the basis of aggregate scores derived from tests that are intended primarily as a measure of individual students.”

Love the example of coaches who should have played the sport, and would love to dream that the journalist in question will think about talking more to teachers and less to “experts.”

Paul, an excellent posting, in part because you raise a very significant point about the lack of professional educational expertise among most (in my experience) education reporters. Schools and teachers are easy-pickings when grabbing a sensational headline.

Excellently covered.

>

Reblogged this on The Academe Blog and commented:

Here’s a terrific piece on the flaws in media coverage of education:

To Nichole Dobo I would say that indeed it IS a problem that reporters are not former teachers (or former anything else they report on – [NOTE: I am a former reporter]). By coming from the outside of any endeavor you can look at and look at but still cannot see what you are looking at. In the case of educational reporting I think you need a good five years teaching to begin to understand enough to know where to go and how to “see” education. At three years you will think you are getting it. At five years you are beginning to know how much you don’t know.

In any case having been a radio and newspaper reporter (late 1960’s and mid 1970’s) during the 1990’s, as a software developer I was interested to see reporter’s stories on the business I worked for. I was even more interested to note that the owners and honchos would read the same reporters’ stories on other businesses and apply a triangulation of their own to “handicap” and re-interpret those stories based on their own knowledge of how wrong the reporting was on our company.

As a photographer, when I began dancing (social) in the mid 1990’s I brought the camera along and gradually changed from being a photographer (close up, medium, etcetera “photo metrics”) to a social dancer looking for what I saw in dance. Later, as I took up shooting performance dance I learned some deeper lessons, starting with tap dancing. Until my first tap classes I thought I had seen enough dance movies, read enough and watched enough that I could shoot performance.

Just prior to my first tap class I watched a Gene Kelley documentary and thought he was okay but nothing really clicked for me. After six weeks of stumbling and learning where to shift balance and how to delicately and clearly and sharply produce taps I again watched that documentary (just bored and put it in the tape player). Suddenly the lights came on. Suddenly I was in a totally new sensory experience as I watched the very same material I had watched cluelessly before. I could really hear the taps cleanly and I could really watch the movements and distinguish them from mere movement.

It was really an aha for me. Now I heard the dance. Then I took (again, stumbled through) adult beginning ballet and flamenco and so forth. (Very, very beginning) Each time I felt a “quantum leap” in my photography because now instead of merely pointing a camera at some dancers and trying to shoot on some motion I was really hearing (very important to seeing) and seeing dance. I now framed for dance and not for a standard photo definition (i.e. close up, head and shoulders, etc. – which I equate to the wrong metrics to measure classes and teachers). The physical embodiment of the activities gives me a base of information to use in taking pictures that I could not have otherwise. I also go beyond mere technique shots by going to rehearsals to learn the piece and the context of any narrative in the piece which adds depth and understanding to my shooting.

I can tell you no editor can see the difference but the dancers can see – and they tell me.

Thanks for the article.

I just received a reply for a similar charge, I laid, at the education news site “The Hechinger Report” I took issue with the fact that of their sizable writing staff, only two had some time teaching k-12 and that was amounted to less than 4 years. They were kind enough to reply to my complaint, and said that they were providing education information to a wider audience, that my comparison to journals, blogs, & news-feeds on the topic of medicine is mostly provided by

people with medical credentials, and that The Hechinger Report was not providing the same level of educational information to a pedagogically astute audience. I also said that the education reform movement had become an industry, staffed almost exclusively by people with no actual teaching experience.

American policy makers, think tank wonks and politicians believe that since they were once students, and or parents, that they are qualified to dictate education policy.