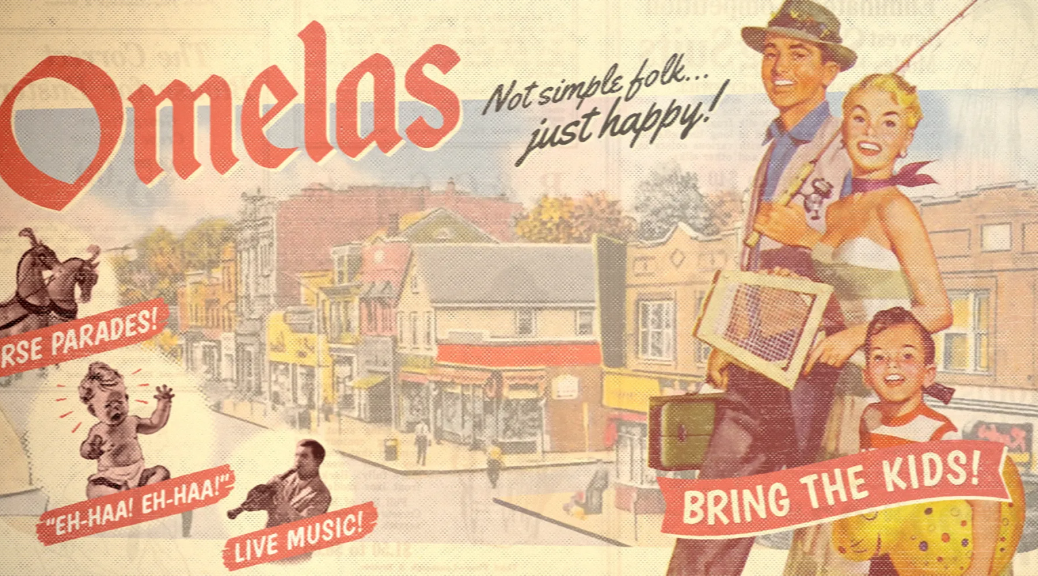

“With a clamor of bells that set the swallows soaring, the Festival of Summer came to the city Omelas, bright-towered by the sea,” opens Ursula K. Le Guin ’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.”*

The reader soon learns about a people and a land that leave the narrator filled with both a passion for telling a story and tension over the weight of that task:

How can I tell you about the people of Omelas? They were not naive and happy children—though their children were, in fact, happy. They were mature, intelligent, passionate adults whose lives were not wretched. O miracle! but I wish I could describe it better. I wish I could convince you. (p. 278)

The narrator offers an assortment of glimpses into these joyous people and their Festival of Summer, and then adds:

Do you believe? Do you accept the festival, the city, the joy? No? Then let me describe one more thing. (p. 280)

The “one more thing” is a child, imprisoned in a closet and its own filth—a fact of the people of Omelas “explained to children when they are between eight and twelve, whenever they seem capable of understanding”:

They all know it is there, all the people of Omelas. Some of them have come to see it, others are content merely to know it is there. They all know that it has to be there. Some of them understand why, and some do not, but they all understand that their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery. (p. 282)

And how do the people of Omelas respond to this fact of their privilege at the expense of the sacrificed child? Most come to live with it: “Their tears at the bitter injustice dry when they begin to perceive the terrible justice of reality, and to accept it” (p. 283)

But a few, a few:

They leave Omelas, they walk ahead into the darkness, and they do not come back. The place they go towards is a place even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness. I cannot describe it at all. It is possible that it does not exist. But they seem to know where they are going, the ones who walk away from Omelas. (p. 284)

Le Guin’s sparse and disturbing allegory has everything that science fiction/ speculative fiction/ dystopian fiction can offer in such a short space—a shocking other-world, a promise of Utopia tinted by Dystopia, the stab of brutality and callousness, and ultimately the penetrating mirror turned on all of us, now.

At its core, Le Guin’s story is about the narcotic privilege as well as the reality that privilege always exists at someone else’s expense. The horror of this allegory is that the sacrifice is a child, highlighting for the reader that privilege comes to some at the expense of others through no fault of the closeted lamb.

In the U.S., we cloak the reality of privilege with a meritocracy myth, and unlike the people of Omelas, we embrace both the myth and the cloaking—never even taking that painful step of opening the closet door to face ourselves.

What’s behind our door in the U.S.? Over 22% of our children living lives in poverty through no fault of their own.

While Le Guin’s story ends with some hope that a few have a soul and mind strong enough to walk away from happiness built on the oppression of the innocent, I feel compelled to long for a different ending, one where a few, a few rise up against the monstrosity of oppression and inequity, to speak and act against, not merely acquiesce or walk away.

Le Guin, U. (1975). The wind’s twelve quarters. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

*Previously posted at The Daily Kos October 30, 2011, slightly revised here.

I love Le Guin, and I’ve heard of this story but never read it. Now I will. What a powerful connection you make here to progressive ed. reform, that is real reform. Well done!

Some readers of the it suggest that those who “walk away” may not be such a positive thing, as they are still DOING NOTHING to help the child in question. If they really were benevolent they would upset the natural order of things and save the child.

Yes. Exactly

That’s a good point. The story presents a complex moral quandary. I actually taught it to me eighth graders this year in an abridged format.

True enough. Silence doesn’t actually solve anything. It may lessen, or stop, the blow for YOU, but it doesn’t change the fact that others may still fall victim to it. Or, in this case, the child will not be saved, and the people of Omelas are still living their lives happily at the expense of the child.

Try reading “Magnificence” by Estrella Alfon (a short story where the protagonist (also) chose silence to protect their reputation).

Preparing lecture notes for class tomorrow … brought me to this site. I agree with Alex (as stated above). Walking away seems like such an apt metaphor–it is so much more passive than actually taking a stand. Reminds of how people don’t even make eye contact with the homeless around our campus. Can’t wait to talk to my class about this one. I work in Detroit and I have a number of social work majors in the class. Should be fruitful discussion!

Does the author contradict herself when she says “the treason of an artist : a refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain”, with the ending? Her art centers Arron’s evil and pain and rejects the happiness she described as laughable. Or do you think she is just being scarcastic ?

I read it as a critique of Utilitarianism.

Reblogged this on kreymerisms.

I understood this to be a world in which the situation with the child just WAS. By choosing to walk away, those people are rejecting that reality and accepting their own pain. I think her point is not so much about the suffering of others, but about our complacency and complicity. There could certainly be a story told about a rebellion that aims to rescue the child. But this story is about people making the difficult choice to not profit from the suffering of others, even when it’s the social norm to do so.

Then again, I am a passionate le Guin fan and might just be making excuses for her. I mean, she was writing this forty years ago; maybe she’d take a different approach now. I know she has revisited and addressed some of the unconscious sexism in her earlier work.

It’s ironic that this story plays out in society today on a slightly different scale. There are so many in todays world that believe a Utopian Society can exist on the shoulders of the working class. Some labor daily in support of those who have no motivation to work finding it easier to remain Entitled. Most know it is happening but no one wants to stop it and there are some that won’t admit it is happening even though they themselves remain entitled. Self perpetuating happiness at the expense of someone else.

Reblogged this on Dick van der Wateren and commented:

Een stuk over het aangrijpende verhaal “The ones who walk away from Omelas” van de Amerikaanse auteur Ursula K. Le Guin van haar bundel The Wind’s Twelve Quarters (1976). Het is een allegorie over privilege en hoe dat ten koste gaat van zwakkeren die niets kunnen doen aan de ongelijkheid. Het verhaal kan een prachtig uitgangspunt zijn voor een serie lessen of een vakoverstijgend project over sociale en economische ongelijkheid.