[Header Photo by Andrew Neel on Unsplash]

Over my 40-year (so far) career as a teacher, I have spent the bulk of that time teaching adolescents and adults to write.

An inordinate amount of that effort focuses on a great deal of unlearning since many writing assignments for students are exclusively student behaviors, not authentic practices or producing authentic artifacts.

This semester I am teaching two first-year writing seminars and an upper-level writing/research course. All of these students are in the midst of submitting cited essays.

This is the time of unlearning the “research paper.”

For the upper-level course, students work through an authentic process of choosing a topic, searching for their primary and secondary sources, submitting an annotated bibliography, and then submitting a cited essay (an analysis of media coverage of an educational topic).

Throughout that process, I note that, for example, the annotated bibliography is for them, a sort of prewriting of the cited essay (not an assignment to submit for a grade). This is an effort to lay the foundation for an authentic process of writing an original analysis grounded in evidence.

Despite my repeated warnings, students in this course still often turn in a first submission that is not a media analysis but a “research paper” on the educational topic. For example, instead of submitting their original analysis of how the media covers dyslexia, they submit a “research paper” on dyslexia.

Concurrent with that assignment, my first-year students are preparing their first formally cited essay (using APA). The essay before this assignment requires them to cite using hyperlinks, again emphasizing an authentic and more common approach to evidence in the world outside of formal schooling.

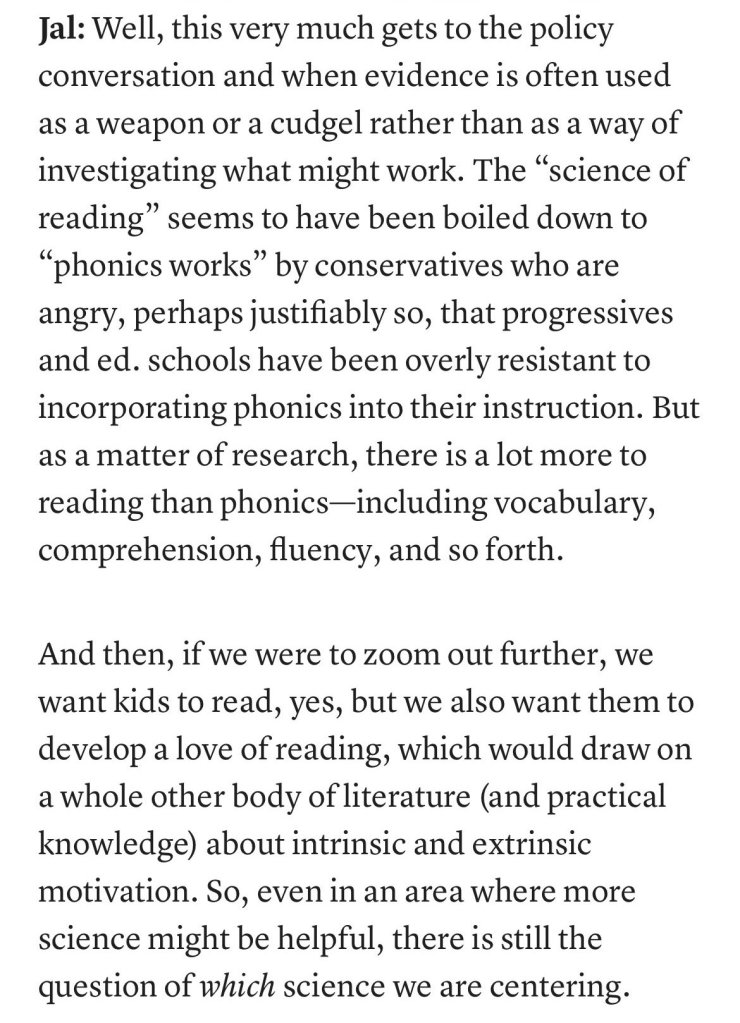

For both first-year and upper-level students, however, the urge to write a reductive and stilted “research paper” is deeply engrained from their K-12 schooling.

One consequence of that artificial experience and template is extremely cumbersome style that includes students writing about their “sources” instead of using their sources as either the focus of their analysis or evidence for their claims.

For example, these sorts of sentences are common:

- Extensive scientific research has been conducted to determine if ADHD is the result of genetics or environmental factors. While this research has shown some correlation between certain genes or environmental factors and the onset of ADHD, the results remain inconclusive (Thapar et al., 2012).

- Various studies and scholarly research conducted surrounding the pipeline expose the oppressive and discriminatory systems and beliefs involving law enforcement and unforgiving disciplinary policies within schools that are continually pushing students, especially students of color out of schools.

- One article I read pushed for dialogue in their congregational community surrounding the mental health of black parishioners.

- Journalists for mainstream media sources have argued that standardized testing adds a lot of stress and without many benefits.

- Published scholarly work has concluded that testing is necessary, and journalists Donnelly (2015) and Silva (2013) back up these views.

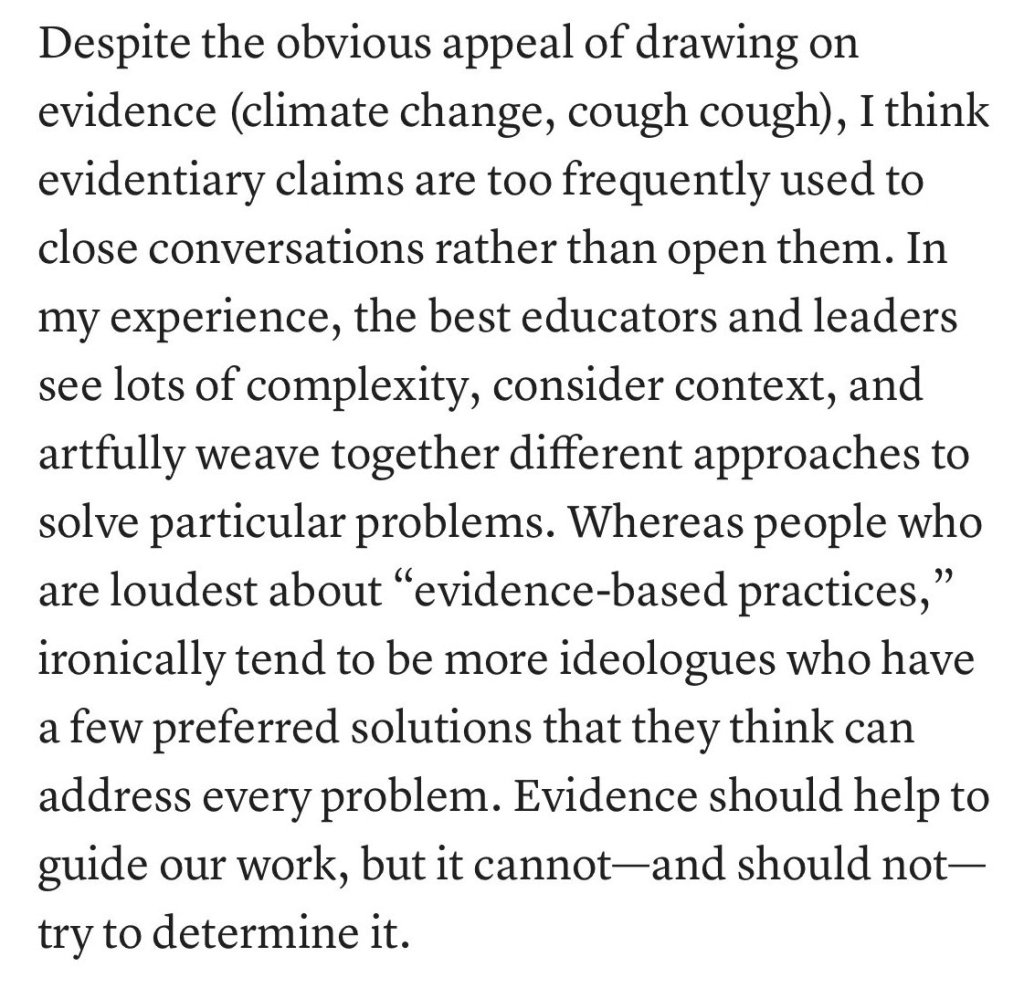

This sort of meta-writing—identifying that scholars do research, treating the sources for an assignment as “my sources,” acknowledging that the student has done the research or reading—is a failure of the students to understand both the nature of cited writing and their own obligation as a writer of scholarship.

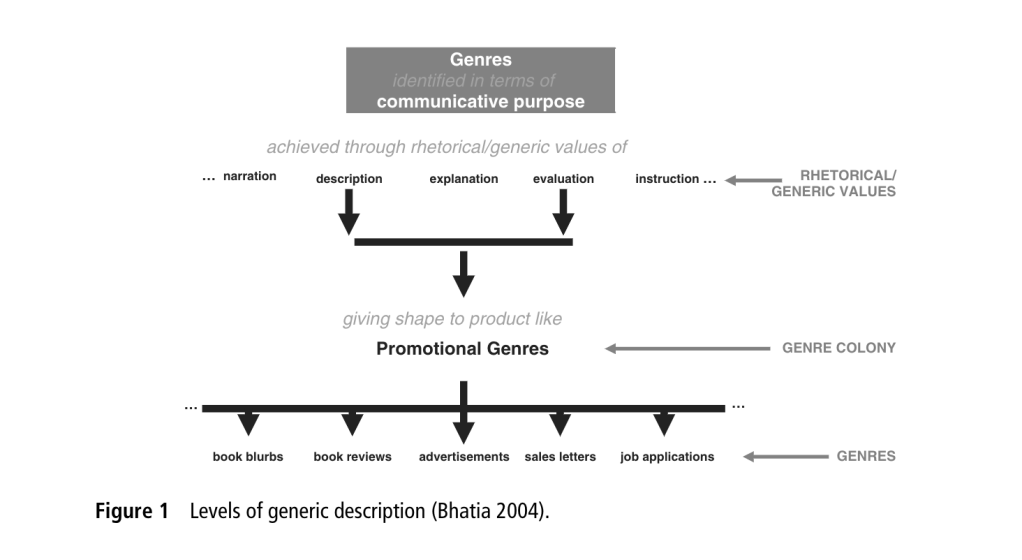

The upper-level course has a very challenging assignment that requires students to understand different types of sources and to write in different styles within the cited essay.

For these students, they have to gather evidence of media coverage of an education topic (the primary evidence of their analysis) while also having a body of scholarly sources that serve as the foundation of that analysis.

The brief literature reviews forces them to focus on the patterns in those scholarly articles, which provides the lens for analyzing the media coverage.

In the media analysis and evaluation sections, then, students must incorporate textual analysis, which requires a much greater sophistication than the examples above.

Here is the expanded guide I have created for those students to navigate the stylistic shifts and the use of evidence in cited essays:

Media Analysis Guidelines (EDU 250)

For 8-10 pages, a proposed structure:

Opening – about 1 page (2-4 paragraphs); be sure to include essay focus on media

[ ] Open with a specific narrative that focuses reader on your educational topic (and possibly use a media example).

[ ] Prefer shorter paragraphs (throughout essay).

[ ] Thesis must focus on media analysis. Prefer identifying questions you will answer about media portrayal of educational topic. [Do not refer to “the literature” or “research.”]

Literature Review – 2 pages; focus on *patterns* in the sources (write about your topics, not the sources); must be fully cited (prefer synthesis and avoid presenting one source at a time) and address all scholarly sources included in references

[ ] Discuss the patterns found in the scholarly evidence. [Do not refer to “the literature” or “research.”]

[ ] Do not write about your “sources”; write about what the evidence shows concerning your educational topic.

[ ] Primarily focus on a synthesis of your scholarly sources; do not walk through one source at a time.

[ ] All scholarly sources must be included, and you must fully cite using APA.

Media Analysis – 2 pages; focus on *patterns* in the media and include several examples; directly identify media outlets and journalists

[ ] Discuss the patterns found in media coverage of your educational topic.

[ ] Identify journalists and media sources specifically; choose some key quotes to show readers evidence of media coverage patterns.

[ ] Must cite fully in APA.

Media Evaluation (identify if media claims are valid or not) – 2 pages; this is the most important goal of the essay so evaluate the media coverage by implementing your knowledge of the scholarship (do not refer to “research” or “sources”); must be fully cited

[ ] This is the key section where you show whether or not the media coverage is valid (supported by research) or not. You must connect media patterns with the scholarly research.

[ ] Do not refer to “my sources,” the “research,” or the “literature.” Use your scholarly sources to evaluate media coverage.

[ ] Must fully cite throughout in APA.

Closing/Conclusion – about 1 page (2-4 paragraphs); must emphasize essay focus, media analysis

[ ] Return to a concrete or specific example from media.

[ ] Maintain focus on media analysis and give your reader something to do with your analysis/evaluation.

This assignment seeks to offer students an experience with what is common in academic and scholarly writing (graduate-level work and published scholarship). The assignment guidelines are too much of a template for my liking, but I am aware that many real-world scholarly works conform to such template or narrow guidelines (see this work of mine written to a strict template).

For both my first-year and my upper-level students, however, what I am seeking is how to foster in them greater autonomy and authority as writers and scholars.

My students’ cited essays are never called “research papers,” students always have choice about topics for their essays and must generate their own thesis/focus for the assignment, and my feedback supports these students incorporating evidence (sources) as ways to build their authority as writer and scholars.

For example, we work on fairly simple stylistic shifts that create authority and move cited essays beyond the research paper:

From this:

Research has shown that standardized testing interferes with both teaching and learning, increases student frustration, and leads to a classroom mindset focused more on grades than on actual learning of material (Wilson, 2022).

To this:

Standardized testing interferes with both teaching and learning, increases student frustration, and leads to a classroom mindset focused more on grades than on actual learning of material (Wilson, 2022).

Students have far too many experiences at the K-12 level that use inauthentic writing assignments (such as the “research paper”) as a mechanism for assessing if students have acquired skills—finding and analyzing sources, implementing academic citation, etc.

Those approaches have the goals reversed.

Students as developing writers and scholars need to acquire those skills in the service of their writing and expression; the cited essay is the thing we are seeking, and their authority as writers/scholars is the most important aspect of our feedback and (if necessary) assessment.

Can a student organize and focus an examination of a topic or idea in ways that are compelling and grounded in valid claims?

To do that well, academic and scholarly writing demands citation that serves to support the authority of the writer.

Ultimately, the urge in students to write about their sources is a reflection of their not yet understanding their autonomy as humans, writers, or scholars.

Students as writers must be allowed the full experiences of being a writer and thinker, guided of course by teachers of writing. But we as teachers of writing often do far too much for the student and ask far too little of those students.

Few students will move on from formal schooling and be academic or scholarly writers. What we must provide them with, then, is writing experiences that support their coming to embrace their autonomy and authority as thinkers along with the ability to express themselves in ways that are credible and compelling.

Thomas, P.L. (2019). Teaching writing as journey, not destination: Essays exploring what “teaching writing” means. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.