Social media are filled with bad political takes and far too much sexism and racism passed off as “It was a joke!”

Often in the same post.

But none of that can stand in the way of some good ol’ grammar, mechanics, and usage snark. Let’s take for example Benjamin Dreyer‘s interactions over Rob Lowe making a multi-level fool of himself on Twitter:

The. Period. Goes. Inside. The. Quotes. Period. 🇺🇸 https://t.co/vIRpTDa1Xa

— Benjamin Dreyer (@BCDreyer) February 10, 2019

Narrator’s voice: He didn’t just get to use an Oxford comma. https://t.co/UsOXTxSl4U

— Benjamin Dreyer (@BCDreyer) February 10, 2019

This Twitter discussion fits well into Dreyer’s recent release of Dreyer’s English and the perennial grammar wars (a bit of a misnomer since these wars between prescriptivists and descriptivists span across grammar, mechanics, and usage).

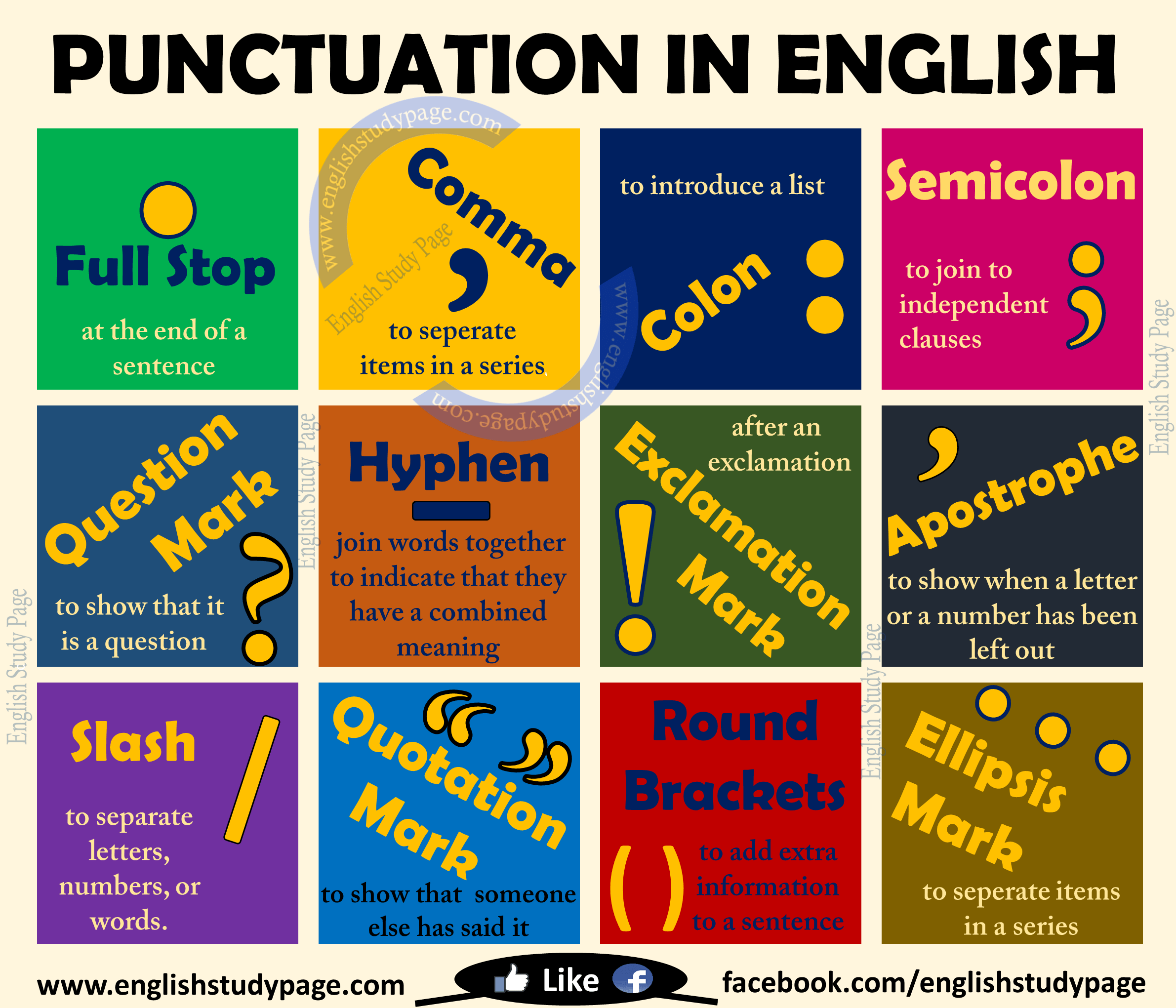

As Dreyer explains, punctuation placement in relationship to quote marks has different conventions in American and British usage:

- I recommend that students avoid making adverbs into adverbs, such as using “secondly” instead of “second.” (American convention of period inside the closing quote mark.)

- I recommend that students avoid making adverbs into adverbs, such as using “secondly” instead of “second”. (British convention of period outside the closing quote mark.)

These differences, I think, are excellent entry points into helping students copyedit their own work better, but also into fostering conventional awareness of language use (instead of a rules-based approach).

I typically discuss the American/British difference before moving to the placement of punctuation in the context of quote marks as an issue of meaning, for example:

- Standard English includes puzzling constructions such as, “I am being clear, aren’t I?”

- Did you say, “My preferred name is Stephen”?

The question mark should remain, as in the first example, inside the closing quote mark to reflect that the quote itself is the question. In the second example, the entire sentence is the question, and the quote a statement; thus the question mark remains outside the closing quote mark.

All in all, these adventures in prescriptive versus descriptive approaches to language conventions may still feel like much ado about nothing to students, who often write because they are required to write and who simply don’t find the distinctions all that important.

The general public communicates moment by moment aloud and in text littered with so-called mistakes while also having almost no loss of communication.

And to be blunt, Rob Lowe’s problems in his Tweets are far less about his lack of understanding punctuation placement—and trying to show off about the Oxford comma but falling flat—and far more about his glib racism.

We descriptivists tend to argue that language conventions are a secondary issue to expression, although, as I explain below, it is nearly impossible to separate expression from conventions.

And so, this Twitter flurry over punctuation and quote marks provides another excellent entry point into helping students understand the role of conventional and purposeful language in establishing your credibility and authority as a writer.

As I have expressed before, some of the best lessons I ever learned about responding to student writing have been grounded in understanding how Advanced Placement graders are trained when scoring written responses.

One convention of writing about the action of fiction is to use present tense verbs—a contrast to using past tense verbs in detailing history.

However, at an AP training session, we were encouraged not to focus on the convention but to look for students being consistent. In other words, verb tense shift (dancing around from present to past without purpose or control) was a reason to lower a score, to identify the writing as less sophisticated.

I thought about this when I read Dreyer’s responses on Twitter because I still stress to my students that understanding punctuation placement in relationship to quote marks is mostly a problem for their credibility and authority as writers when the final punctuation dances around throughout the essay—some times inside, some times outside, with no rhyme or reason.

As a writing teacher who seeks ways to foster my students as autonomous and eager writers who also have a healthy attitude about language (an inclusive and historical awareness of conventions), I seek opportunities like Dreyer’s chastising Lowe as entry points into exploring conventional awareness and how language use cannot be disentangled from writer credibility and authority.

I often come back to again and again to making the case that credibility and authority are driven by writer control and purpose.

The dancing comma implies a lack of control, or purpose.

My argument, then, is not to browbeat students into being correct, but to encourage them to find ways to make their voices heard and appreciated.

And maybe to avoid being called out on social media, and to avoid stepping in the original mess again over and over.